Le contrat naturel

January 22 - February 28, 2026

Robert Adams

Lewis Baltz

Katinka Bock

Gerard Byrne

Jef Geys

Mimmo Jodice

Louise Lawler

Sophie Nys

Marina Pinsky

Ed Ruscha

Thomas Struth

Larry Sultan & Mike Mandel

Jeff Wall

Henry Wessel

Joe Zorrilla

With Le contrat naturel, Galerie Greta Meert presents a group exhibition that does not so much as to illustrate the eponymous publication (1990) by French philosopher, essayist and historical thinker Michel Serres (1930-2019), but activate it as a framework for thought. Written at a historical turning point, when the ecological crisis was already manifesting itself but not yet fully anchored in political and legal structures, Serres’ essay marks a fundamental repositioning of humans in relation to their environment. The exhibition takes this shift seriously and functions as a field of inquiry in which both the totality and the inherent limits of Serres’ philosophy are tested.

The focus is on photographic works, a method that offers direct and seemingly objective access to the world, but at the same time leaves room for ambiguity and critical distance. Photography records, but does not explain; it shows, without forcing conclusions. It is precisely in this tension that Serres’ critique of the classical social contract resonates. For some artists in this selection, photography is their exclusive working method; for others, it is an additional avenue within a more meandering practice. In all cases, the medium functions as an instrument of attention, not of illustration.

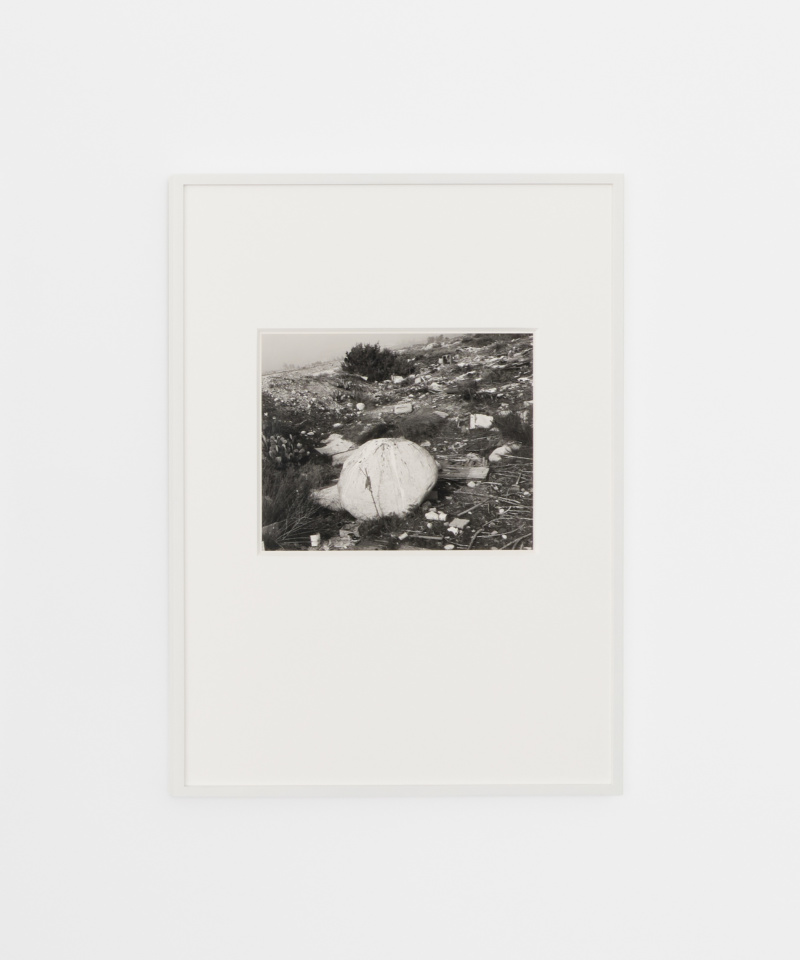

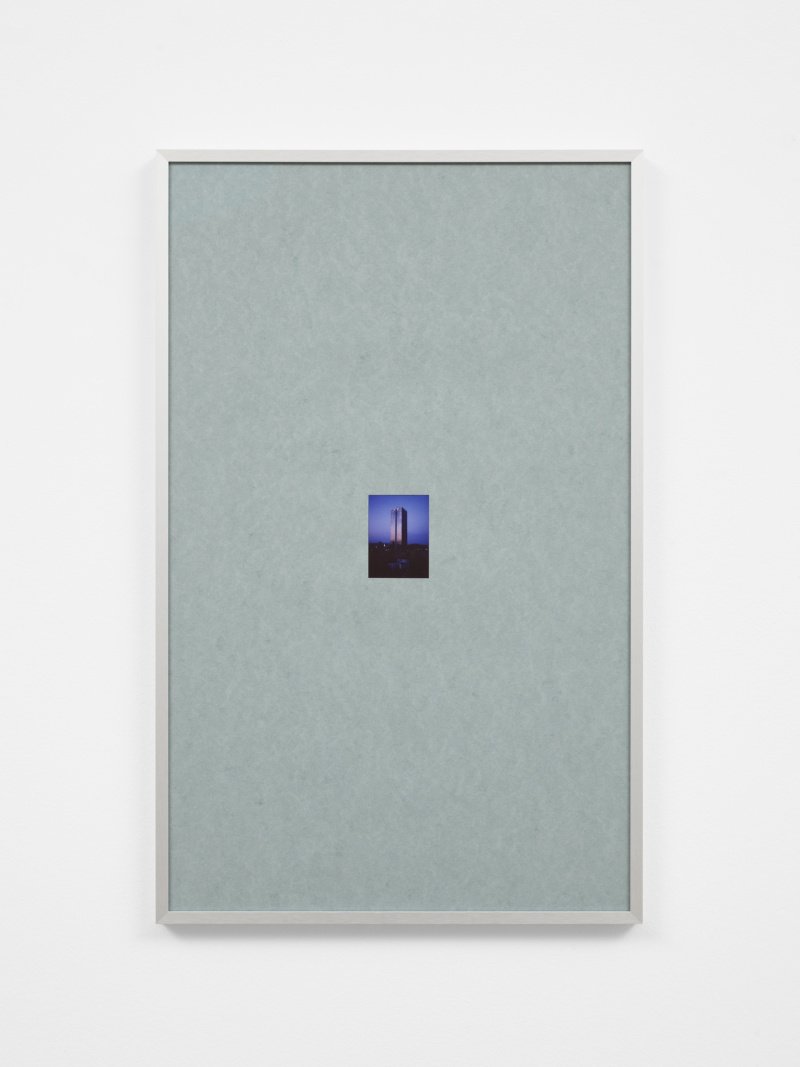

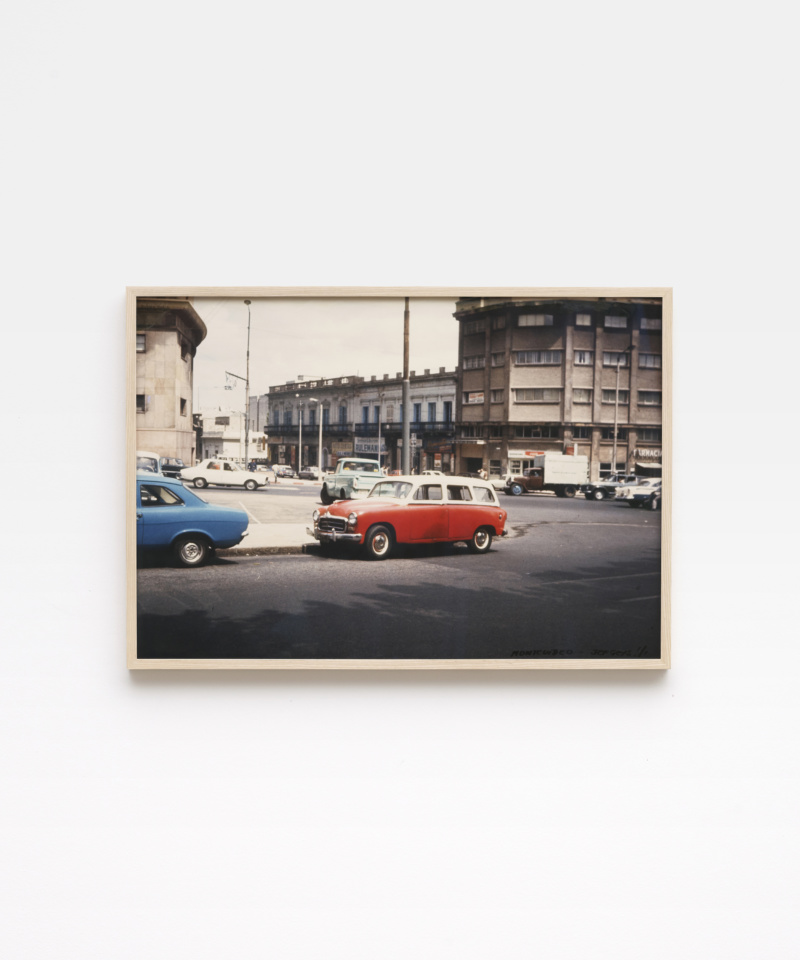

A first important thematic line is the shift from nature as backdrop to nature as witness. The images on display often feature urban views, zones of transition or damaged landscapes. They point to the natural environment, not as idyllic or untouched, but as a bearer of human traces. Nature appears here as a silent but present partner in a history of exploitation and transformation. This ties in closely with Serres’ plea to no longer regard the earth as a passive backdrop, but as an active entity within a reciprocal relationship.

In addition, the exhibition explicitly approaches urbanisation as a historical process. The exponential growth of cities over the past 250 years is revealed as a layered and often fragmentary narrative. What these works show is not self-evident progress, but an accumulation of decisions, infrastructures and economic interests that have become spatially entrenched. City and nature do not appear as opposites, but as intertwined systems.

A third connection with Serres’ thinking lies in the implicit criticism of the failure of the classical social contract. Because this contract exclusively regulates the relationship between people, the non-human world remains without rights. The exhibition makes the consequences of this asymmetry tangible: landscapes in which nature is reduced to raw material, residual product or logistical surface. The scale and systematic nature of these interventions suggest that ecological damage is not an exception, but is structurally embedded in dominant models of production and progress.

Photography functions here as a narrative medium that makes responsibility visible without taking an explicit stance. Places are connected to broader, often global systems, so that cause and effect can no longer be defined locally. Responsibility appears as relational and spread across time and space.

Finally, both in Serres’ text and in this exhibition, the focus shifts from representation to implication. Visitors are not only confronted with images, but also involved in the convention they evoke. Le contrat naturel functions here not as a closed concept but as an open proposal, namely a visual negotiation about care, reciprocity and the conditions for a shared future.