Galerie Greta Meert is honoured to present Liam Everett’s recent body of work in He Loved Him Madly. This exhibition continues Everett’s long-standing exploration of painting as an accumulative, experimental practice — one that thrives on instability, transience, and the residue of gesture. What emerges on the surface of his canvases is not a static image, but the layered memory of action: an imprint of movements, erasures, and resistances enacted over time.

The title He Loved Him Madly is borrowed from Miles Davis’s 1974 composition, a sprawling, mournful elegy to Duke Ellington. Davis’s piece resists conventional structure: it drifts through repetition, silence, and improvisation, unfolding slowly rather than reaching resolution. The resonance with Liam Everett’s work is immediate. Like Davis, Everett cultivates an art of deferral and transience, where presence is inseparable from erasure, and where meaning emerges gradually, in time. The title therefore acts as both echo and homage: a phrase that expands beyond its musical origin to frame Everett’s own devotion to painting as a fugitive, unstable, and yet profoundly vital practice.

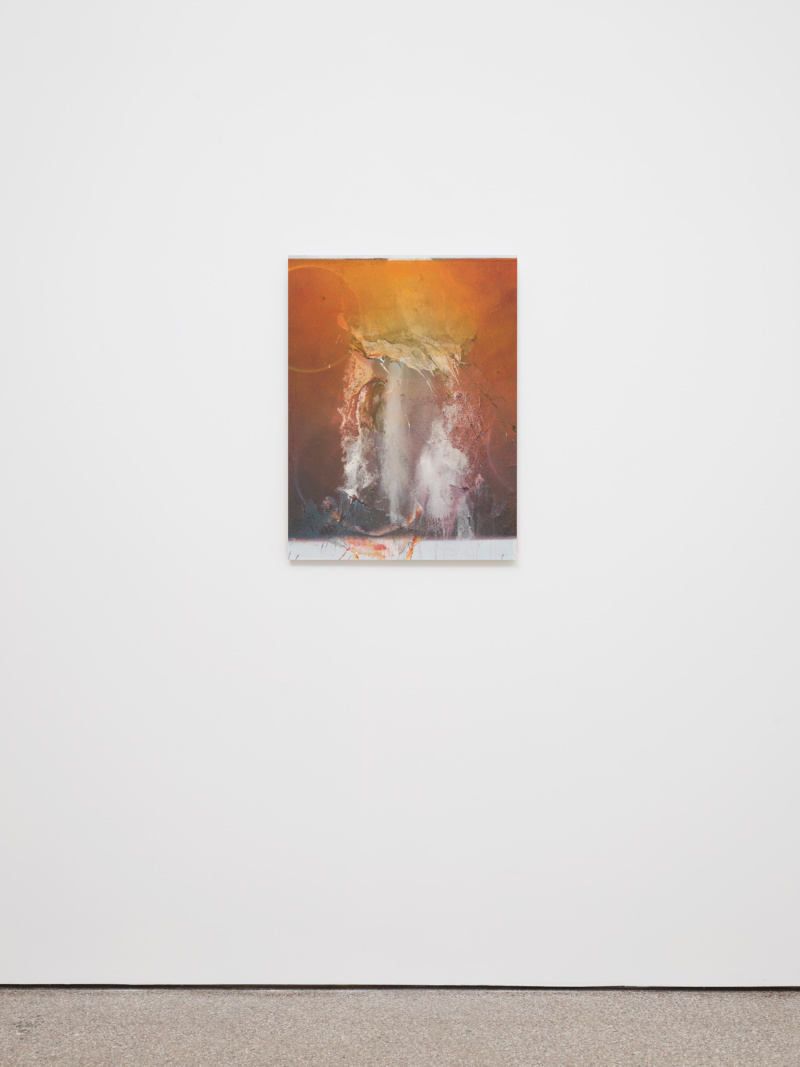

At the centre of this exhibition are Everett’s large-scale tondos, circular canvases ranging from around 165 to 195 cm in diameter, and accompanied by smaller, more intimate works. These paintings do not resolve into images so much as accumulate traces. Layers of pigment, alcohol, salt, and solvents are repeatedly applied and withdrawn, producing luminous, corroded surfaces that seem simultaneously geological and atmospheric. Here, painting is not an additive process but a cycle of attrition and renewal. Each act of erasure is as crucial as application, preserving the sense of a surface never fixed, never fully present, always at risk of dissolving.

This technical approach situates Everett’s practice in proximity to performance. It all traces the memory of gesture: movements of pressure, removal, endurance. What is visible is not a singular mark but the residual energy of repeated actions, accumulated until the surface itself becomes an archive of duration. The paintings ask to be experienced slowly, their shifting layers unfolding in response to light, position, and time. In this way, they establish a performative temporality: what remains is less an image than the persistence of gesture.

Everett’s titling — often poetic, oblique, and evocative — further complicates the relationship between object and language. Titles such as Ra folding, nazar se or not a sound, only the embers function not as explanations but as murmurs, amplifying the paintings’ enigmatic materiality. In this way, his work resists fixed interpretation, instead inviting a phenomenological engagement, one attuned to the flickering contingencies of light, memory, and the body’s movement around these radiant canvases.

In He Loved Him Madly, this dialogue between painting, performance, and language is underscored by the connection to Davis’s composition. Both practices dwell in repetition and variation, both rely on erasure and silence as structuring forces, and both demand a durational mode of attention. Just as Davis created an extended space of mourning that resists closure, Everett’s works sustain a precarious equilibrium between appearance and disappearance.

The tondos, with their non-rectilinear format, intensify this sense of suspension. They recall celestial bodies or ancient artefacts, yet their surfaces remain fragile, trembling with imperfection. Monumental in scale yet ephemeral in material presence, they resist resolution and invite contemplation. They hover between being and fading, always on the threshold of becoming something else.

In this sense, Everett’s practice embodies a paradox: painting as both monumental and momentary, both grounded in material experiment and charged with the memory of action. He Loved Him Madly positions these works not as final statements but as echoes, resonant surfaces in which process, gesture, and language converge, and where painting continues to exist as a living, uncertain, and profoundly durational art.

Liam Everett articulates painting as a practice of endurance, erasure, and resonance. Through his technical processes of layering and removal, his performative gestures inscribed in the surface, his poetic and enigmatic titles, and his dialogue with Miles Davis’s music, Everett offers painting as a site of ongoing negotiation — between presence and absence, image and memory, devotion and dissolution. These works resist the closure of fixed meaning, instead inviting us to inhabit the unstable, flickering space where gesture lingers as echo, and where each act of looking renews the performance of painting itself.