Press Release

Greta Meert Gallery presents the third solo exhibition of the American sculptor and essayist Brandt Junceau (1959, New York).

The gallery exhibition places his recent work in the context of the terra cotta studies, and works still in-progress, from which they developed. His practice, making use of moldmaking and casting of successive states, makes repetitive “essais” from a given form. Each attempt is unique, none are definitive, none are conclusive, and all of them are open to further departures.

The studies, seen together, resemble a litter of archeological finds. The presentation of smaller works on the long table in the Galerie; figures, masks, “sirens” and “birds,” in terra cotta and bronze, also resembles the artist’s studio. His sculpture is in frequent contact with the past, in a continuing “imaginary archaeology.” In the past 12 months he made use of a DAAD Residence in Berlin to study the figurative sculpture of the last century, and the ancient world. He admits to “a funny sense of time” and says that, for him, “this morning and the distant past are not that far apart.” He does not “refer” to the past; it erupts in his work.

The bronze Stehende, nearly flat, like a freestanding drawing, or a dark mirror, is something like an after-image of the past. It was recently shown in Berlin, installed immediately facing the Sommalier Torso (1912) of Georg Kolbe, across the room, the two pieces, 99 years apart, in reflective correspondence.

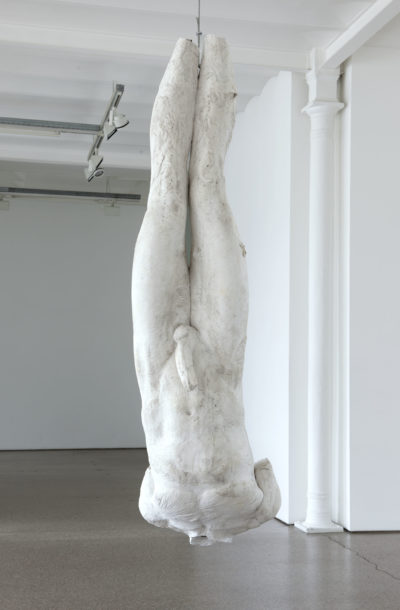

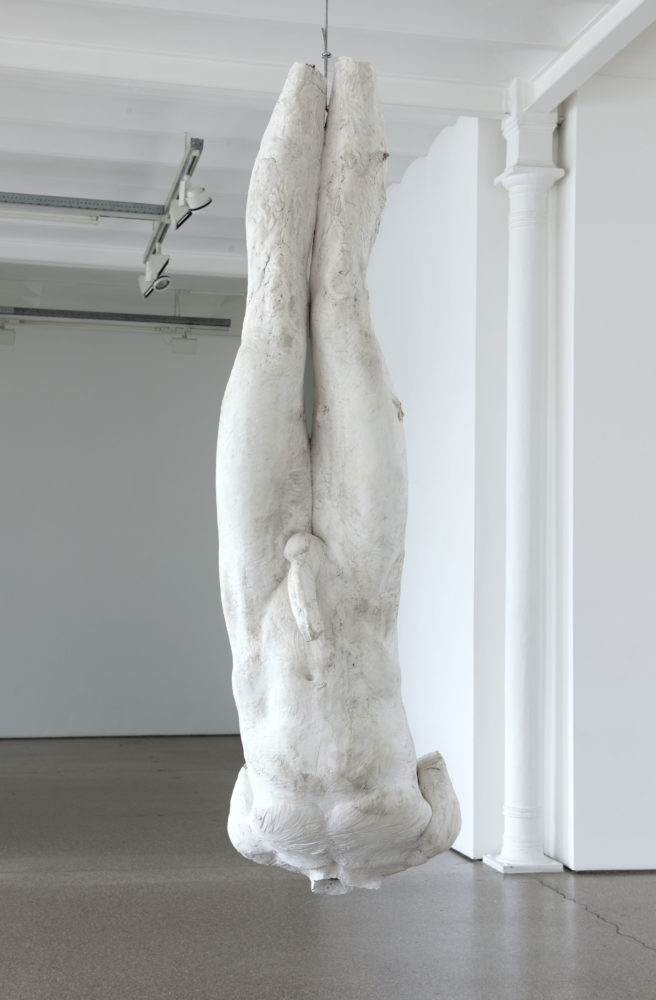

The large white plaster figure (Hangende), and the bronze Torso developed through terra cotta studies, which were produced vertically, suspended head-down, like fresh-killed game. Really the artists’s recent work with the human figure derives from the life-size birds he exhibited at the Galerie in 1995. He has subjected the over-life size male body to the overwhelming force he applied to small birds. The large figure witnesses, unmistakeably, the themes of physical terror and sexual extremity of the Apollo and Marsyas legend, and the brute pathos of Rembrandt’s Slaughtered Ox. Their predicament is extreme, but the artist said these pieces are “an extreme expression of a general human condition. I think we are all hunted down, overwhelmed and destroyed against our will, and before our time.”

The ardent, aroused, vitality of the hanging figure, otherwise an apparent victim, is uncanny, but the unheimlich is the domain of so much of the artist’s work. The heads, busts and masks, which confront us with a raw, unfamiliar consciousness neither simply human nor purely irrational are one example. Like them, the “sirens” touch upon the theme of Lampedusa’s short story Lighaea, which the artist regards as the best-ever essay on the ancient world, and a kind of key to his own work.