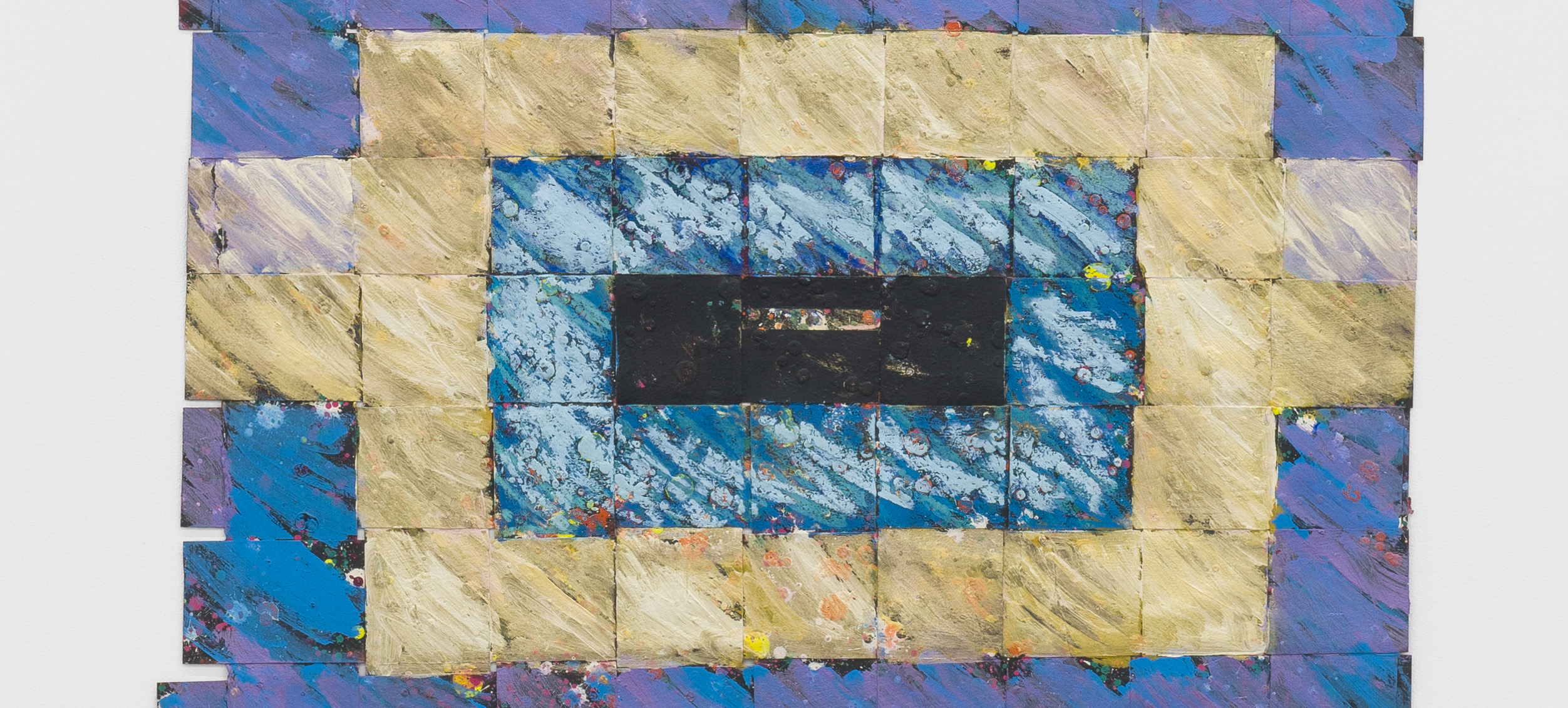

Alonzo Davis, Outside-In ⏤ detail, 1992

Alonzo Davis

b. 1942 in Tuskegee, AL, USA

d. 2025 in Largo, MD, USA

d. 2025 in Largo, MD, USA

Alonzo Davis, who passed away in January this year, left behind a remarkable example of a life deeply engaged with his community and with the urgent politics of his time, and a body of artwork that draws expansively on historical traditions and pan-global influences.

With his brother, Dale Brockman Davis, in 1967 Alonzo Davis opened the Brockman Gallery in the middle-class, Black neighbourhood of Leimert Park, in south Los Angeles. Just two years after the Watts Riots, south L.A. was rebuilding itself not only literally but socially and culturally too. Over the next two decades, the Brockman Gallery was the most important venue for Black artists in the city, exhibiting artists such as David Hammons, Noah Purifoy, Elizabeth Catlett, Romare Bearden and Senga Nengudi, at a time when many other galleries in the city were not receptive to their work. While those influential figures have now entered the art historical canon, the Brockman Gallery served another important function, by exhibiting and selling work by a broad population of working artists and makers, thus building a modest, sustainable economy around creative production in this community.

With his brother, Dale Brockman Davis, in 1967 Alonzo Davis opened the Brockman Gallery in the middle-class, Black neighbourhood of Leimert Park, in south Los Angeles. Just two years after the Watts Riots, south L.A. was rebuilding itself not only literally but socially and culturally too. Over the next two decades, the Brockman Gallery was the most important venue for Black artists in the city, exhibiting artists such as David Hammons, Noah Purifoy, Elizabeth Catlett, Romare Bearden and Senga Nengudi, at a time when many other galleries in the city were not receptive to their work. While those influential figures have now entered the art historical canon, the Brockman Gallery served another important function, by exhibiting and selling work by a broad population of working artists and makers, thus building a modest, sustainable economy around creative production in this community.

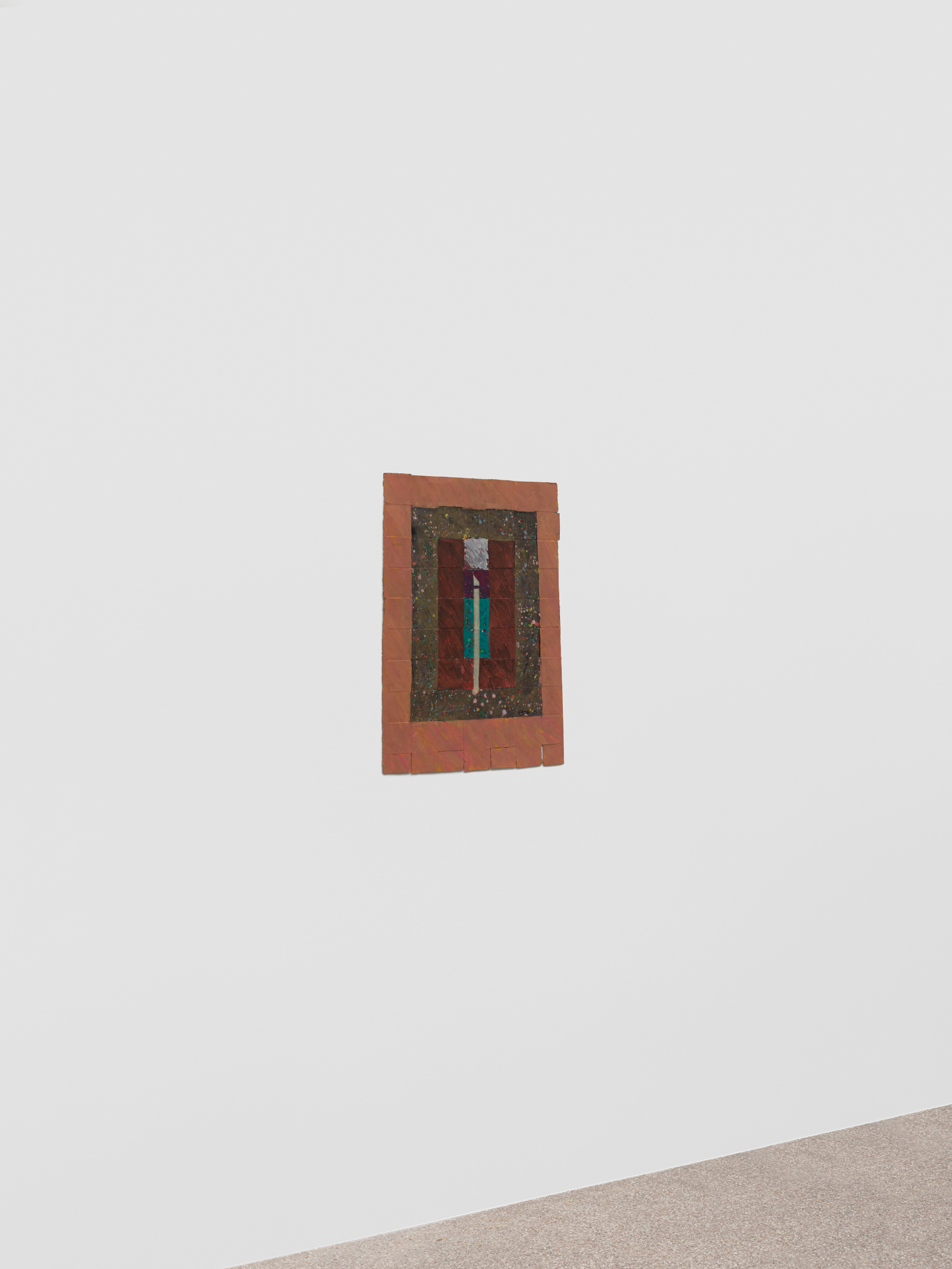

Installation view, Alonzo Davis: Blanket Series, 2022 – 2023, parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles, CA (USA)

© Alonzo Davis. Image courtesy parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles. Photographer: Ed Mumford

© Alonzo Davis. Image courtesy parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles. Photographer: Ed Mumford

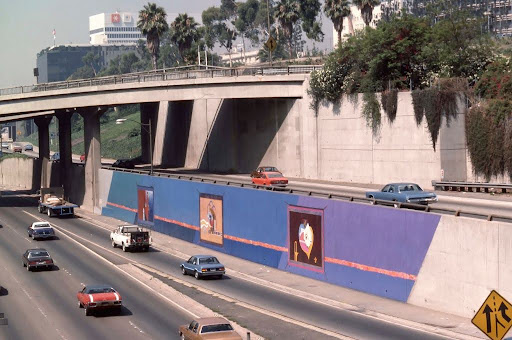

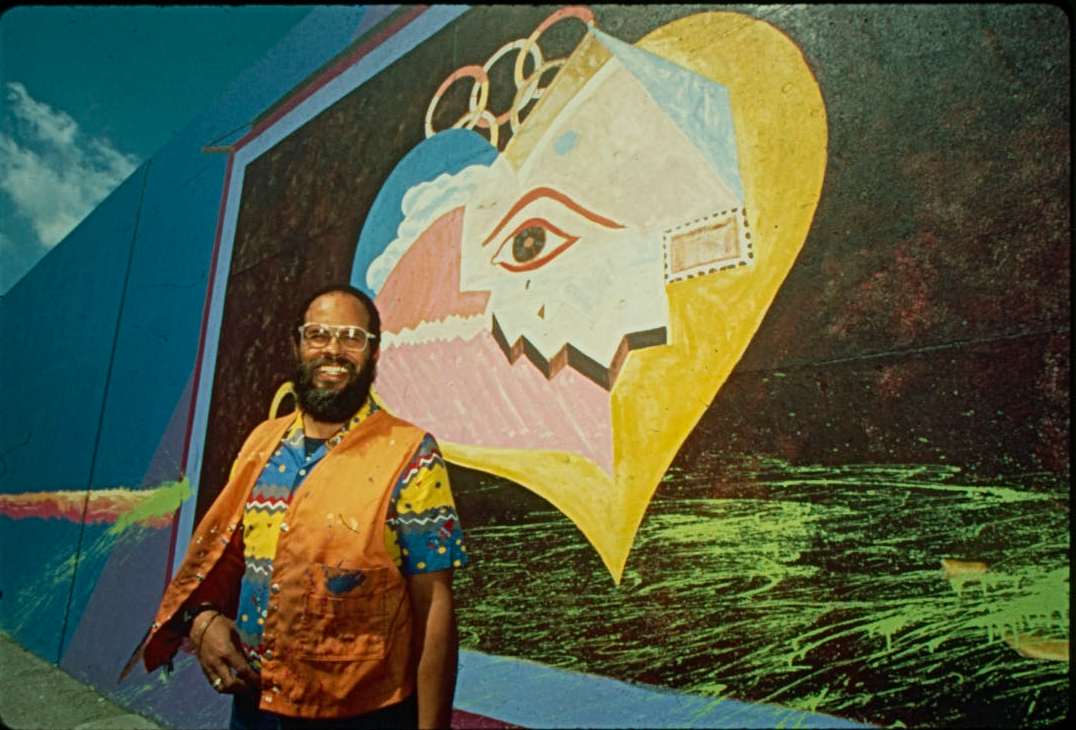

While running the gallery, Davis undertook various mural commissions, including painting a wall beside a Los Angeles freeway to commemorate the 1984 Olympic Games. After he left the Brockman Gallery in 1987, Davis moved to Sacramento to run a public arts programme. He subsequently focused on teaching, becoming dean of the Art Institute of San Antonio, Texas, and later was appointed dean of the Memphis College of Art, Tennessee.

In his own artwork, Davis declined to represent directly the social and political fervour of post-Watts Los Angeles. Instead, his work in mixed media was internally reflective and open-ended, even when representational elements – such as a silhouette of Africa, or of his own head – became containers for other abstract effects.

Installation view, Alonzo Davis: Blanket Series, 2022 – 2023, parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles, CA (USA)

© Alonzo Davis. Image courtesy parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles. Photographer: Ed Mumford

© Alonzo Davis. Image courtesy parrasch heijnen, Los Angeles. Photographer: Ed Mumford

The most profound expression of Davis’s broad concerns may be his “Blanket” series, which he began in the 1980s. In these works, Davis wove strips of painted paper and canvas to create objects that exist somewhere between wall-hanging textiles and reliefs, between painting and sculpture. Despite the work’s tribute to various African and Asian traditions of weaving, from Kente cloth to Berber rugs to Persian or Chinese carpets, Davis manages to imbue the seemingly humble objects with a human warmth (the comfort of a blanket) and with a sense of vast cosmic and spiritual wonder.

Alonzo Davis. Image credit: Brockman Gallery Archive, Los Angeles. Public Library Special Collections, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Thanks to Parrasch Heijnen Gallery for their collaboration on the group show Once The Block Is Carved, There Will Be Names.