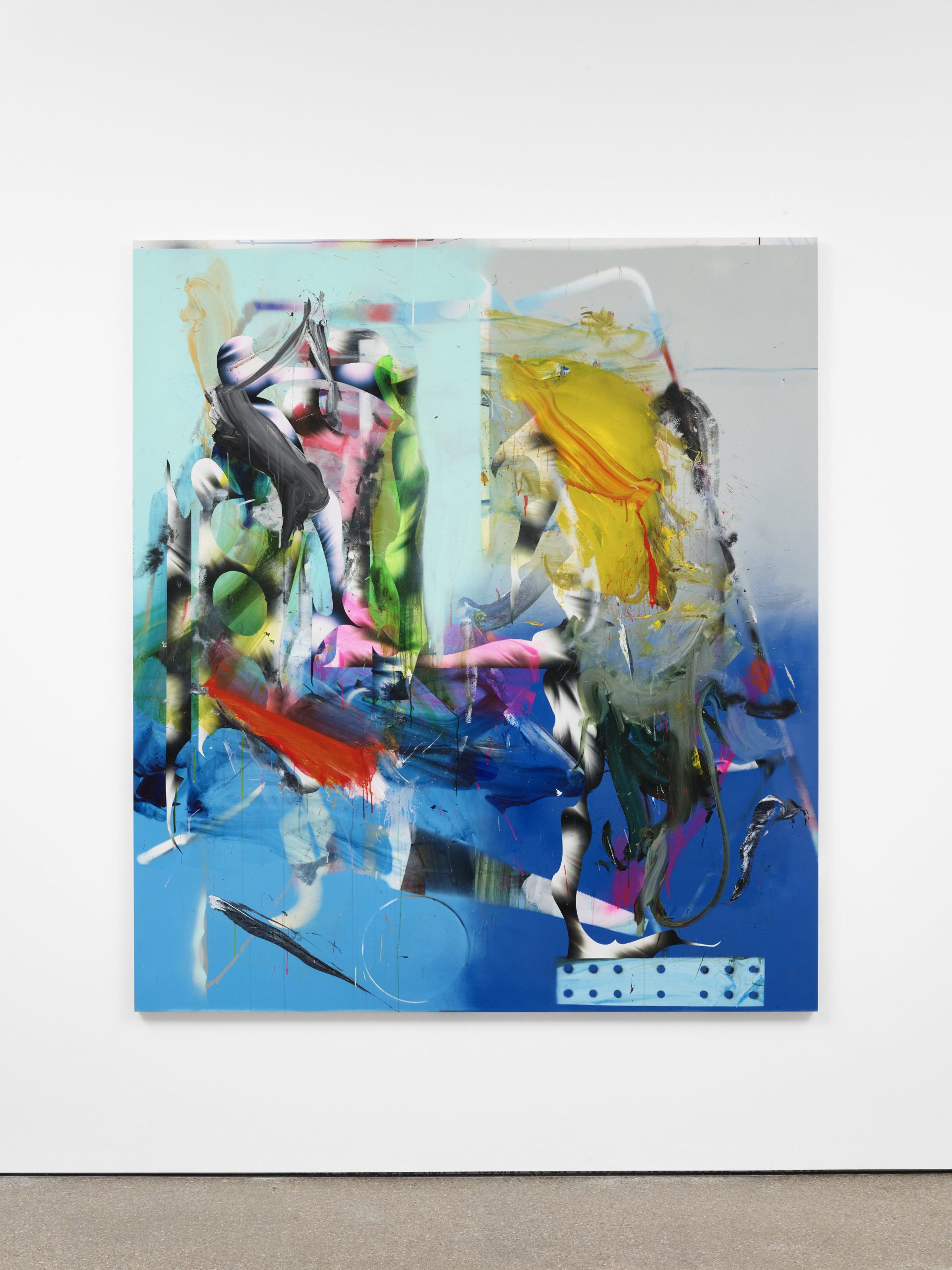

Liam Everett, Untitled (unmade overtones) – detail, 2022, ink, oil, acrylic, sand and alcohol on linen

Liam Everett

Four Corners

Four Corners

November 24 ⏤ January 15, 2023

Four Corners, the title of Liam Everett’s viewing room, refers to the four directions—North / South /

East / West or four points on a stage and the “missing” painting, as there are only three visible in the exhibition. The fourth is always the “not-yet”. Or maybe, it refers to the invisible wall that delineates the frontier between spectators and the spectacle?

For this online viewing room, independent curator Natasha Boas conducted an interview with Liam Everett in the artist’s studio, a former barn located 80 kilometers North of San Francisco in West Sonoma County looking out towards the Pacific Ocean.

East / West or four points on a stage and the “missing” painting, as there are only three visible in the exhibition. The fourth is always the “not-yet”. Or maybe, it refers to the invisible wall that delineates the frontier between spectators and the spectacle?

For this online viewing room, independent curator Natasha Boas conducted an interview with Liam Everett in the artist’s studio, a former barn located 80 kilometers North of San Francisco in West Sonoma County looking out towards the Pacific Ocean.

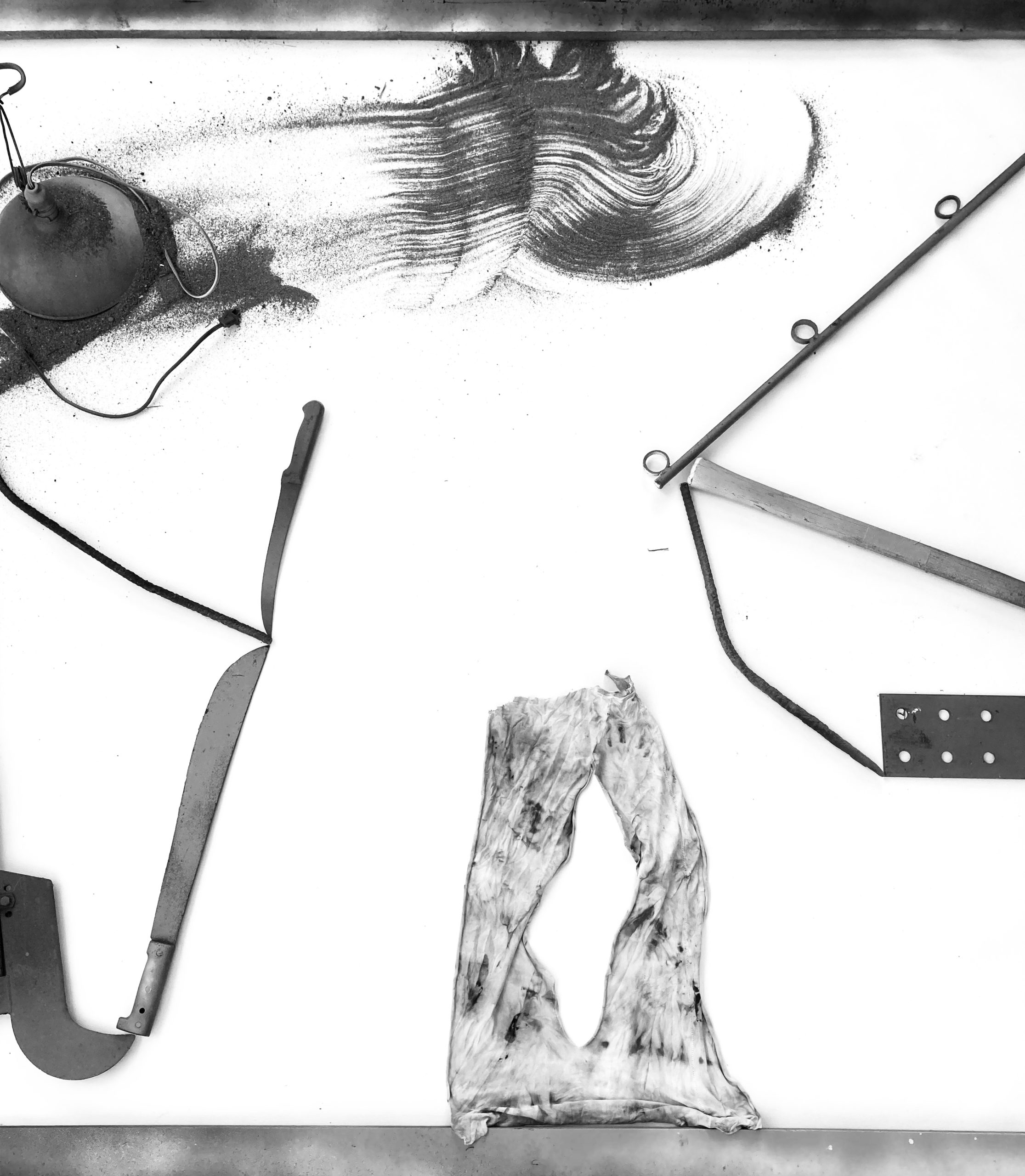

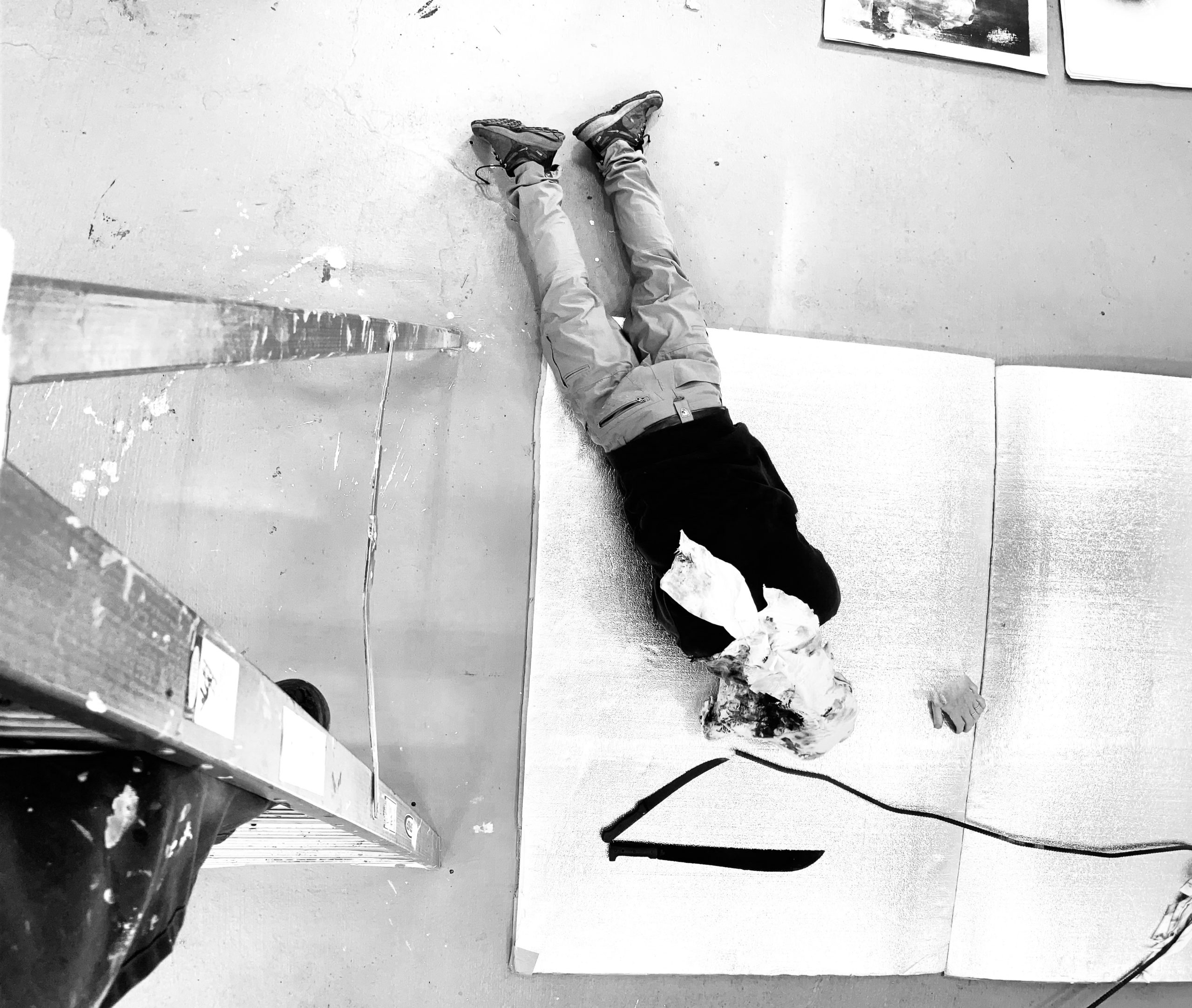

Studio Liam Everett – Autumn 2022, Sebastopol, CA

Photography by Emilia Turner

Photography by Emilia Turner

Born in 1973 in Rochester, New York, Liam Everett lives and works in Northern California.

Liam Everett’s abstract mixed-media painting and sculpture result from a process of steadfast and repetitious application and erasure, employing non-traditional methods to apply — and caustic substances to remove — painstakingly developed layers of paint and composition. Inspired by the dynamic alchemy of the natural environment in California, this method makes plain the interactive properties of the substances on the canvas — how they counteract, preserve, or react to one another.

Liam Everett’s abstract mixed-media painting and sculpture result from a process of steadfast and repetitious application and erasure, employing non-traditional methods to apply — and caustic substances to remove — painstakingly developed layers of paint and composition. Inspired by the dynamic alchemy of the natural environment in California, this method makes plain the interactive properties of the substances on the canvas — how they counteract, preserve, or react to one another.

Installation view, Four Corners, Liam Everett, Galerie Greta Meert, 2022

Studio Liam Everett – Autumn 2022, Sebastopol, CA

Everett works with ideas around everyday objects holding multiple meanings. “I’m interested in the potential for a highly recognizable object to transform itself in such a way that it begins to shed its original utilitarian personae. As soon as these objects are transferred to a two-dimensional surface, there is this kind of tragi-comical transmutation that occurs in which they start to take on alternate connotations.

I think of it as de-evolving, where the object is divorced of its first reality and then inevitably begins to develop new valences, ones that I didn’t anticipate. They often end up looking like sad props culled from the backstage of an agit prop theatre. The intention with this material is not just to repurpose it but to also rearrange the ideas and concepts that I associate with them.”

I think of it as de-evolving, where the object is divorced of its first reality and then inevitably begins to develop new valences, ones that I didn’t anticipate. They often end up looking like sad props culled from the backstage of an agit prop theatre. The intention with this material is not just to repurpose it but to also rearrange the ideas and concepts that I associate with them.”

Liam Everett, Untitled (unmade overtones) – detail, 2022, ink oil, acrylic, sand and alcohol on linen

Natasha Boas: I see the apparition of new objects that I haven’t seen before in your work and I was wondering if you could talk about them: dominos, saws, trowels, hammers, wedges…. How do they operate in the context of your recent interest in working through, studying and researching Jungian analysis?

Liam Everett: I never saw what you just called dominos as such. It is somewhat uncanny as the actual image is not of a domino per se but instead it is a print remnant made by pressing a steel mending plate, which is normally used as framing hardware to connect beams. The fact that the image of dominos showed up for you really ties in to the Jungian sand-tray images I have been collecting. Jungian-based sand-tray therapy uses trays filled with sand and a variety of miniatures that can be placed in the trays. You use your imagination to create three-dimensional scenes or stories that bypass the thinking and analytical brain and can bring to light what may otherwise not be visible.

Liam Everett: I never saw what you just called dominos as such. It is somewhat uncanny as the actual image is not of a domino per se but instead it is a print remnant made by pressing a steel mending plate, which is normally used as framing hardware to connect beams. The fact that the image of dominos showed up for you really ties in to the Jungian sand-tray images I have been collecting. Jungian-based sand-tray therapy uses trays filled with sand and a variety of miniatures that can be placed in the trays. You use your imagination to create three-dimensional scenes or stories that bypass the thinking and analytical brain and can bring to light what may otherwise not be visible.

Studio Liam Everett – Autumn 2022, Sebastopol, CA

N.B.: What about the orbs in each painting — you call them running moons — I can’t help but think they turn the paintings into some kind of landscape.

L.E. : Actually what you refer to as moons are simply crude imprints from five gallon plastic buckets. But you are right they do point to landscape.

N.B.: So we would be looking down into the buckets.

L.E.: Exactly. The irony is that the bulk of these paintings are made as I’m looking down upon them. I’m literally on top of the substrate in many cases, standing on the surface, something like an actor on a stage or a temporary platform.

L.E. : Actually what you refer to as moons are simply crude imprints from five gallon plastic buckets. But you are right they do point to landscape.

N.B.: So we would be looking down into the buckets.

L.E.: Exactly. The irony is that the bulk of these paintings are made as I’m looking down upon them. I’m literally on top of the substrate in many cases, standing on the surface, something like an actor on a stage or a temporary platform.

Liam Everett, Untitled (the piano drop) – detail, 2022, ink oil, acrylic, sand and alcohol on linen

N.B.: What is your relationship to time in terms of your process?

L.E.: I connect the time problem to speed. And there is a very particular speed that I’m looking for, not just in my paintings but when I approach art in general, whether it’s dance or film or literature. I’m really craving a certain kind of tempo. It’s the reason that most of my paintings in the studio fail because I realize I’ve taken over the tempo of the work and for me that’s the beginning of the end. This is also why I use these particular objects. I’m looking for a scenario in which the painting starts functioning in such a way that it establishes its own timing and then I’m just kind of moving around it and learning from it. I think these sets of problems are based in time.

L.E.: I connect the time problem to speed. And there is a very particular speed that I’m looking for, not just in my paintings but when I approach art in general, whether it’s dance or film or literature. I’m really craving a certain kind of tempo. It’s the reason that most of my paintings in the studio fail because I realize I’ve taken over the tempo of the work and for me that’s the beginning of the end. This is also why I use these particular objects. I’m looking for a scenario in which the painting starts functioning in such a way that it establishes its own timing and then I’m just kind of moving around it and learning from it. I think these sets of problems are based in time.

N.B.: You work on the floor?

L.E.: Yes, I have to because otherwise these things will fall apart or fall off. When I finally put them up on the wall their reality completely changes. The literal perspective of how I’m seeing these things takes a dramatic shift… It’s really absurd because if I’m manipulating a thing in one way and then I put it up on the wall, everything that I was directing just dissolves. Out of that rupture are the beginnings of a new narrative that I actually have nothing to do with.

N.B.: Makes sense. Like in the sandbox.

L.E: Yes and to that effect, I feel like this is when the paintings begin to assert themselves.

L.E.: Yes, I have to because otherwise these things will fall apart or fall off. When I finally put them up on the wall their reality completely changes. The literal perspective of how I’m seeing these things takes a dramatic shift… It’s really absurd because if I’m manipulating a thing in one way and then I put it up on the wall, everything that I was directing just dissolves. Out of that rupture are the beginnings of a new narrative that I actually have nothing to do with.

N.B.: Makes sense. Like in the sandbox.

L.E: Yes and to that effect, I feel like this is when the paintings begin to assert themselves.

Liam Everett, Untitled (the piano drop) – detail, 2022, ink oil, acrylic, sand and alcohol on linen

Studio Liam Everett – Autumn 2022, Sebastopol, CA

N.B.: You use, in terms of your process, this idea of repurposing. Can you address this?

L.E.: This goes back to a point in my practice when I really came to the conclusion that I didn’t want to lead a painting with ideas, instead I wanted the paintings to be led by their surroundings or immediate context. That was maybe 10 or 15 years ago. I had had a really frustrating day in the studio and just started to throw everything I had on top of the painting: chairs, buckets, debris, tools, anything I could find in the space. Then I began outlining and making marks around this material, almost as a way of taking inventory or creating an archive of what was in the studio.

I was trying to generate a series of questions regarding the nature of practice, on a kind of ontological level: What does it mean to be present with practice in the studio? How can this presence or presencing be sustained? And perhaps most important, what does this heightened state of presence look like, especially within the constraints of the two-dimensional?

L.E.: This goes back to a point in my practice when I really came to the conclusion that I didn’t want to lead a painting with ideas, instead I wanted the paintings to be led by their surroundings or immediate context. That was maybe 10 or 15 years ago. I had had a really frustrating day in the studio and just started to throw everything I had on top of the painting: chairs, buckets, debris, tools, anything I could find in the space. Then I began outlining and making marks around this material, almost as a way of taking inventory or creating an archive of what was in the studio.

I was trying to generate a series of questions regarding the nature of practice, on a kind of ontological level: What does it mean to be present with practice in the studio? How can this presence or presencing be sustained? And perhaps most important, what does this heightened state of presence look like, especially within the constraints of the two-dimensional?

N.B.: Like you were recording your process through the inventory of the objects. Where do these objects come from to begin with?

L.E.: Almost all of these tools or images that you see are from things I found here on the land, in the pasture, the orchard, the redwood groves. Some were buried; some were under piles of farm debris that accumulated over the years. Almost all of these relics are broken or missing parts or simply just rusted away.

N.B.: Leftovers, scraps, vestiges… Objects that had lost their use value?

L.E.: Yes, useless objects. But when you pick them up something new happens, there is still a charge. It’s like what Heidegger refers to as the “object at hand.” Once it’s literally in your hand, or has your attention, it suddenly takes on quite a different presence than when it’s not at hand.

N.B.: That’s the title of our talk I have decided: Object at Hand. It says it all.

L.E.: Ironically these defunct objects return to things that are ‘useful’ as they are repurposed as tools to make paintings. I’m looking at a painting that has a hatchet in it and a machete and those were used to clear the slope here, by the previous owners I imagine.

N.B.: Is there something about the ready-made that’s happening as well?

L.B.: I prefer to think about these objects as props. I pick these things up and move them around, like on a stage set. In this way it functions as a choreographic practice. Okay, how do we start? Well, let’s not even ask ourselves that question, let’s allow the space and the objects to direct us in how to move from one corner to the other or how to make a mark or gesture from one section of the painting to the other. The other intention here is to find a way in which the idea and action appear simultaneously, neither preceding the other. For me that’s the biggest struggle in painting: how to make a gesture that is not premeditated.

N.B.: It’s like these objects are indexing the action and referring back to painting because they have become embedded in the process of making the painting.

L.E.: Almost all of these tools or images that you see are from things I found here on the land, in the pasture, the orchard, the redwood groves. Some were buried; some were under piles of farm debris that accumulated over the years. Almost all of these relics are broken or missing parts or simply just rusted away.

N.B.: Leftovers, scraps, vestiges… Objects that had lost their use value?

L.E.: Yes, useless objects. But when you pick them up something new happens, there is still a charge. It’s like what Heidegger refers to as the “object at hand.” Once it’s literally in your hand, or has your attention, it suddenly takes on quite a different presence than when it’s not at hand.

N.B.: That’s the title of our talk I have decided: Object at Hand. It says it all.

L.E.: Ironically these defunct objects return to things that are ‘useful’ as they are repurposed as tools to make paintings. I’m looking at a painting that has a hatchet in it and a machete and those were used to clear the slope here, by the previous owners I imagine.

N.B.: Is there something about the ready-made that’s happening as well?

L.B.: I prefer to think about these objects as props. I pick these things up and move them around, like on a stage set. In this way it functions as a choreographic practice. Okay, how do we start? Well, let’s not even ask ourselves that question, let’s allow the space and the objects to direct us in how to move from one corner to the other or how to make a mark or gesture from one section of the painting to the other. The other intention here is to find a way in which the idea and action appear simultaneously, neither preceding the other. For me that’s the biggest struggle in painting: how to make a gesture that is not premeditated.

N.B.: It’s like these objects are indexing the action and referring back to painting because they have become embedded in the process of making the painting.

Liam Everett, Untitled (reanimator) – detail, 2022, ink, oil, acrylic, sand and alcohol on linen

N.B.: Do you think about collage?

L.E.: Yes but very broadly. I’ve been in a space many times where someone has asked me directly, “Is this collage?” I don’t think of myself so much as a painter as I do a builder. So these paintings are built, they are constructed. That’s also my approach to color. I don’t have a relationship with color in a traditional sense, each color for me represents a certain density and a certain speed and that’s how they’re applied in the way that you would build a structure that you didn’t want to fall down, you know?

L.E.: Yes but very broadly. I’ve been in a space many times where someone has asked me directly, “Is this collage?” I don’t think of myself so much as a painter as I do a builder. So these paintings are built, they are constructed. That’s also my approach to color. I don’t have a relationship with color in a traditional sense, each color for me represents a certain density and a certain speed and that’s how they’re applied in the way that you would build a structure that you didn’t want to fall down, you know?

Liam Everett, Untitled (reanimator) – detail, 2022, ink, oil, acrylic, sand and alcohol on linen

Installation view, Four Corners, Liam Everett, Galerie Greta Meert, 2022

Liam Everett’s work has been included in exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Biennale of Painting, Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens, Deurle, Belgium; U.C. Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive; San Jose Institute of Contemporary Art; CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts, San Francisco. Everett is the recipient of the SECA Art Award at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2017), the Richard Diebenkorn Teaching Fellowship at the San Francisco Art Institute (2013) and the San Francisco Artadia Award (2013). Everett’s work is included in significant international public collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Dallas Museum of Art; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes, France; Fondation Carmignac, Paris; Kistefos Museum, Jevnaker, Norway, and U.C. Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive.

Natasha Boas is a French-American independent curator, writer and scholar based in San Francisco and Paris. Boas holds a doctorate degree from Yale University and she is a visiting professor at UC Berkley and the California College of Art. Specialising in Countercultural movements, Modernist avant-gardes and Contemporary Art, she has worked for and collaborated with international museums and galleries including Centre Georges Pompidou, San Francisco Art Institute, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, Fondation Maeght, Galerie Perrotin , SFMOMA, LACMA. Her writing regularly appears in frieze, ArtForum, and the New York Times.

Studio Liam Everett – Autumn 2022, Sebastopol, CA